What if Eternals wasn’t a failure of Marvel storytelling, but its most radical, visionary film yet? It may have taken me four years to fully realize it, but this movie quietly redefines what it means to be strong, heroic, and a true leader. And the reason so many of us missed it? We were too busy expecting it to be just another entry into the Marvel Cinematic Universe — but we were wrong.

This, dear reader, is my long-overdue Eternals appreciation post.

If you’ve been a long-time reader, it’s a piece that pairs nicely with what I previously wrote about Star Wars: The Last Jedi. It will explore the archetypes of the masculine and the feminine and why I believe Eternals is one of the most interesting superhero movies ever made, precisely because it redefines what strength, power, and leadership can look like within the genre. Ultimately, I believe these generic moves align with global shifts associated with the gradual re-balancing of masculinity and femininity, a redefinition of power, as well as showing us a more sustainable way forward.

In my previous piece about Star Wars, I included this passage from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, which I think will help frame what I’m talking about here:

The world in the past has been ruled by force, and man has dominated over woman by reason of his more forceful and aggressive qualities both of body and mind. But the balance is already shifting; force is losing its dominance, and mental alertness, intuition, and the spiritual qualities of love and service, in which woman is strong, are gaining ascendancy. Hence the new age will be an age less masculine and more permeated with the feminine ideals, or, to speak more exactly, will be an age in which the masculine and feminine elements of civilization will be more evenly balanced.

To me, this quote speaks to how humanity has been led by more masculine tendencies for generations. Wars, colonialism, slavery, unchecked capitalism, environmental destruction — all these things and so much more are tied to the worst manifestations of generally masculine energies: domination, force, individualism, competition, aggression, etc. Feminine energies, on the other hand, include things like creativity, sensitivity, compassion, community, empathy, and being nurturing. Decisions and policies made with archetypically feminine energies tend to look out for the collective good, help ensure greater equity, and nurture the growth of all.

For the purposes of this post, I will refer to the masculine and the feminine in terms of archetypal qualities and traits. People of all genders and sexes are able to express all human qualities and traits. However, generally speaking, masculine traits tend to be more associated with groups of men, and feminine traits tend to be more associated with groups of women. Some of this is a result of socialization, some of it traces its roots to the most ancient stories, histories, and allegories in human history.

Regardless, these energies are at their most productive when they are at a balance, and within the bounds of moderation. Competition is not an inherently evil quality. But take it to the extreme and you can easily bankrupt families, prioritize the accumulation of wealth over human dignity, environmental protection, and worse. Sensitivity can be a powerful way to empathize and connect people, but too much can paralyze and freeze you. The same is true for all the traits I’ve mentioned above.

I believe Eternals taps into this shifting balance in a way I have not seen before in a superhero movie. By focusing the story on Sersi’s gradual embrace of her leadership role in light of her particular non-adversarial powers, Eternals sets forth a clear and impactful stance on the kind of choices, leadership, and actions that can make actual lasting change. Below, we’ll go through a brief plot summary of the film, talk a little more about these masculine and feminine archetypes, and then look at some specific moments from the film that align with a recognition of this shifting balance. Ultimately, I claim that Eternals presents a vision and framework for superheroes that goes against the normative adversarial nature of these narratives. Instead of celebrating the use of force and violence in response to violence, it suggests that there is another way for a more sustainable future. And it uses the characters of Sersi and Ikaris to work through these tensions.

SPOILERS ABOUND.

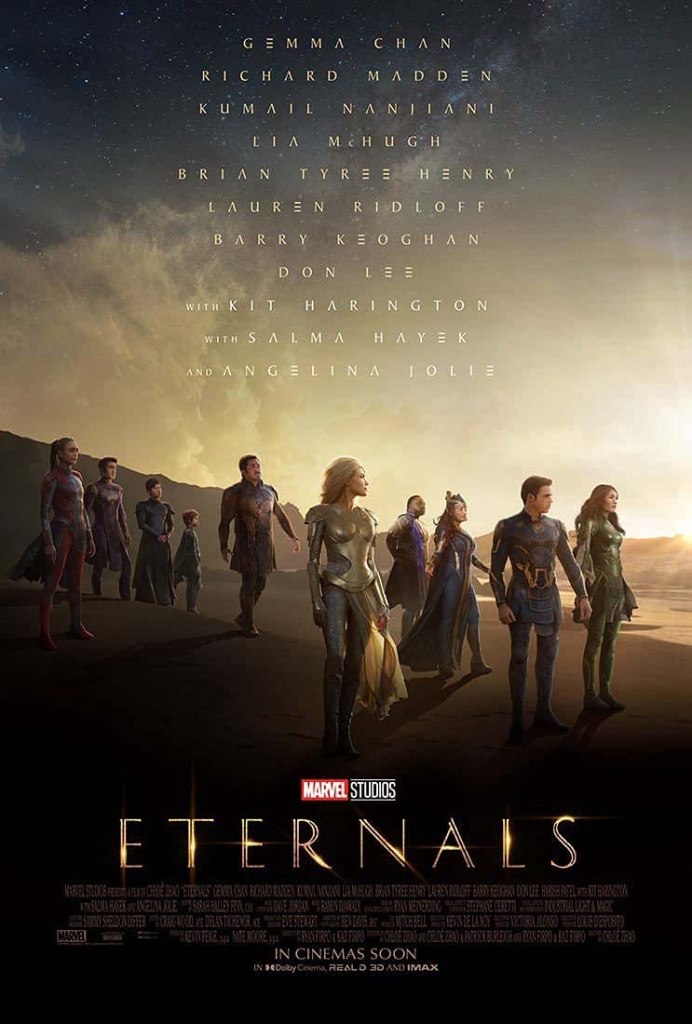

In Marvel’s Eternals, directed by Chloe Zhao, we are introduced to a group of 10 Eternals – immortal beings created by the Celestial Arishem – who are sent to Earth to protect the planet from Deviants, gnarly creatures who hunt and kill people. Or so that’s what they’ve been told. Over the course of the movie, we follow the team across 7,000 years as they fight Deviants – and at times each other – and struggle with interpersonal conflicts as well as the nature of their purported mission. They have incredible powers, live among humans, but are not allowed to interfere in any human conflicts — unless it involves Deviants. Once they think they’ve killed all the Deviants, their leader Ajak sees the toll their mission has taken and orders them all to split up and live their lives on Earth until they are called back home to the planet Olympia.

The team consists of the following Eternals, listed from left to right according to the image above, along with their powers:

- Kingo (played by Kumail Nanjiani) – can shoot energy beams from his hands.

- Makkari (played by Lauren Ridloff) – superspeed.

- Gilgamesh (played by Ma Dong-seok) – a heavy hitter.

- Thena (played by Angelina Jolie) – a skilled fighter/warrior; the inspiration behind the Goddess Athena.

- Ikaris (played by Richard Madden) – basically Superman: he can fly, has super strength, and shoots lasers out of his eyes.

- Ajak (played by Selma Hayek) – the leader of the bunch. She has the power to heal.

- Sersi (played by Gemma Chan) – has the power to change matter.

- Sprite (played by Lia McHugh) – can create illusions.

- Phastos (played by Bryan Tyree Henry) – has the power of invention.

- Druig (played by Barry Keoghan) – mind control.

After centuries apart, and to everyone’s surprise, Deviants show up in the present day, forcing the team to reunite. In the process, they learn Ajak is dead, Sersi is chosen as their new leader, and eventually discover the truth about their purpose. The Eternals were never meant to save Earth, and there is no Olympia. They’re supposed to keep humans alive to help the population grow so that all life can be consumed/destroyed in support of the birth of a new Celestial, whose seed was planted on Earth thousands of years before. Once they learn the truth, Sersi decides to stop the Celestial from being born, a decision that fractures the team between those who follow Sersi (Ajak’s chosen successor), and those who follow Ikaris (the one many assumed would/should have been the successor).

Masculine and Feminine Archetypes

Alright, let’s talk briefly about archetypes. Archetypes come from narratives, stories, symbols, motifs that have been told and retold across time and space, across generations and cultures. According to Carl Jung, archetypes are part of our “collective unconscious.” It’s like these ideas and concepts that we collectively inherit from the previous generation and are kind of automatically keyed into. The fact that they show up over and over again across human history speaks to a certain amount of truth they seem to carry — because why else would people so otherwise disconnected from each other by time and space come up with the same ideas and concepts again and again? I think a lot of people come across archetypes in ELA classes when talking about archetypal characters and narratives in novels: the hero, the trickster, the villain, etc. They appear again and again in story after story, in culture after culture, and they generally share similarities every time they do.

In a similar way, we can look at the masculine and the feminine as archetypes. In ancient myths, inanimate objects and natural processes were given human qualities as a way to help make sense of and explain the world. In this kind of storytelling, men and women also came to represent and stand in for certain categories of qualities and values – what we call masculine and feminine – that were perhaps based on generalized tendencies of the group as a whole. Some of the traits we typically describe as masculine include: assertiveness, physical strength, dominance, bravery, being logical, and independent. Some of the traits we typically describe as feminine include: being nurturing, emotionally strong, collaborative, caring, vulnerable, intuitive, and humble. The masculine takes, while the feminine gives. The masculine dominates, while the feminine submits. The masculine is rational, while the feminine is emotional. The masculine fights, while the feminine surrenders. The masculine acts, while the feminine reacts.

Unfortunately, throughout much of human history, the masculine has been prioritized and celebrated, while the feminine has been demeaned and even villainized. Associating the masculine strictly with men and the feminine strictly with women contributes to false binaries where the two sides are never allowed to co-exist. Men are leaders, which means women must follow. Men are strong, which means women must be weak. Men make decisions in the household, which means women must submit to them. Men take control, which means women must have no control. In all of these examples, the masculine trait is considered the better and more positive of the two. And since the masculine has been historically exclusively tied to men and the male body, it contributes to thinking that men are better too.

History has prioritized masculine powers to the detriment of developing and valuing our feminine powers. We have, in other words, been living in extremes. There has been no moderation. The masculine has been assumed to be the default because, without the feminine to give it some balance, the masculine insists on being the loudest, the angriest, and the most aggressive force in the room. In this extreme expression, the masculine often cares only about winning, and the surest way to win and silence others is to be loud, angry, and aggressive. To force the other side into submission. On the other hand, by its very nature, the feminine does not engage in the same way. The feminine listens, empathizes, nurtures, creates, and encourages dialogue, honesty, and understanding.

In Eternals, the tension between the opposing forces of the masculine and the feminine are represented by Ikaris, who fights, kills, and is dead-set on their mission even after learning the truth, and Sersi, who creates, saves, and shows empathy at every turn. The growing tension between the two characters, their viewpoints, and frameworks, is what ultimately drives the film’s narrative forward.

Sersi and Ikaris as Opposing Forces

The movie opens with an exchange between Sersi and Ikaris that establishes the central tension between the two. They have just been brought into being aboard their ship – the Domo – as it floats out in space. Sersi approaches a window overlooking the Earth and says “It’s beautiful isn’t it?” Ikaris, standing nearby, looks at her and simply replies “I’m Ikaris.” From the jump, Sersi is established as a character who looks outward, beyond herself. She sees Ikaris, she sees the Earth, and her first instinct is to wonder at the beauty of the planet before her, and invite someone to share in that wonder with her — to create a connection. Ikaris, however, responds from a place of self-centeredness. He either doesn’t see or doesn’t care about the beauty and wonder before him. His eyes are laser focused on Sersi, devoid of any affect, and he introduces himself. He does not attempt to connect with Sersi or meet her at her interest – a shared wonder. Instead, he reaches out with his own interest – himself. Within the first 2 minutes of the film, we clearly see the dynamic of their relationship: two people talking past each other because they are coming from entirely different conceptual frameworks — a dynamic that plays out throughout the the rest of the movie.

Over the next 30 minutes, we see the Eternals across time and space in a superheroic montage of sorts that jumps across time: the present day, ancient Mesopotamia, Babylon, and more. It’s a great narrative and expositional tool to introduce the audience to the large cast of characters, their primary traits, and their powers through exciting action sequences. We see Ajak’s thoughtful leadership style and healing powers; we see Ikaris’s apparent invincibility and emotional disconnect; we see Gilgamesh’s hard-hitting force and dry sense of humor; we see Thena’s grace, skill, and fighting prowess; Kingo’s power beams and playful ways; Druig’s rebelliousness and powerful mind-control; Sprite’s pent-up frustrations and her powers of illusion; Makkari’s superspeed and mischievous nature; and Phastos’s intellectual genius and general cautiousness. Across these sequences and vignettes, all nine are shown actively fighting and killing Deviants. But not Sersi.

Throughout the action sequences above, Sersi isn’t killing and destroying — she’s saving, creating, and connecting. She helps villagers develop agriculture, creates water, saves civilians, and cares deeply about their wellbeing. She learns from humans and teaches them in return. This is her superpower: empathy, compassion, community, connection, creativity, and being nurturing. When London seems to be hit with an earthquake and a giant boulder is about to fall on a young girl, she turns it into sand. Face to face with a Deviant, she turns the ground it stands on into liquid and then back to solid, temporarily trapping the creature in the asphalt. When a Deviant causes a city bus to flip over and head straight for them, Sersi turns it into thousands of flower petals, saving the driver inside.

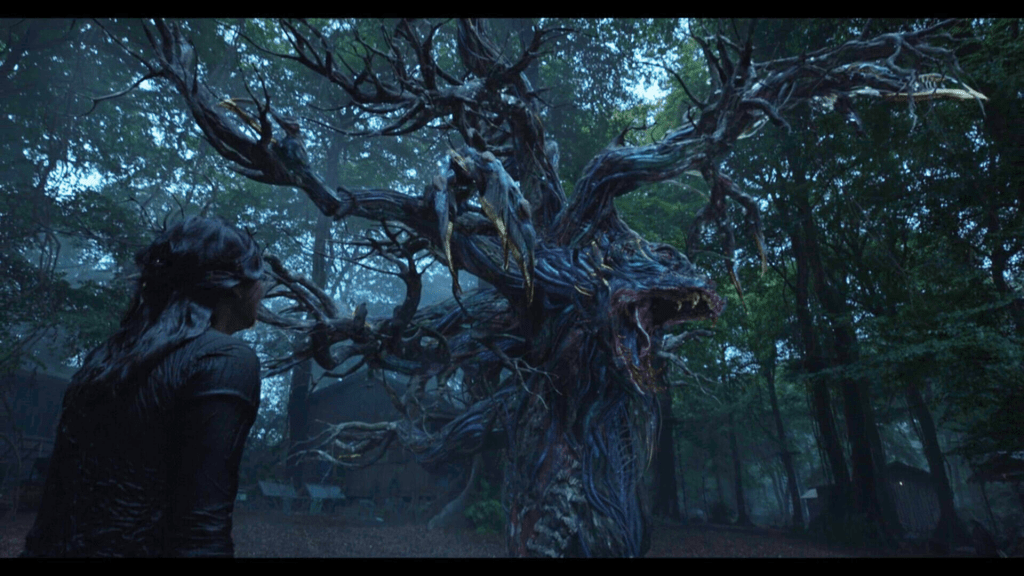

For the majority of the film, Sersi is limited in her power — she says she cannot transform living things. However, in a tense scene where a Deviant corners her in the forest, Sersi surprises herself when she turns a Deviant into a ghastly warped tree. It’s the first time she’s been able to use her powers on a living being, and it’s never fully explained just what changed. Perhaps new powers came with being leader, a natural evolution of her powers, or maybe just the adrenaline of the moment. Either way, I think it’s very telling that even in this one instance where we see her essentially “killing” a Deviant, she essentially gives it a new life as a tree. She turns a living thing that kills into a living thing that gives. Again and again, Sersi refuses to meet conflict with conflict.

Another way to talk about how Sersi’s character pushes back against the common – though fundamentally contradictory – superhero trope of using violence to get to peace, is to talk about normative adversarialism.

Superheroes and Meeting Violence with Violence

Normative adversarialism is the assumption that contests are normal and necessary models for social organization (Check out Michael Karlberg’s amazing book, Beyond the Culture of Contest for more on that!). Adversarialism affects everyone regardless of race, gender, sex, culture, wealth, or ethnicity. It’s everywhere. From zero-sum takes on the economy, to the generally adversarial presentation of the news; from supporting the view that conflict and exploitation are simply a part of human nature to the tendency to criticize individuals more than the validity of their particular ideas; from the extreme nationalism that sustains wars on little other grounds, to the educational system’s focus on outdoing others in grades and achievements; in all these ways and more, adversarialism and conflict remain at the forefront in the day-to-day operations of our present-day society. It’s the assumption that conflicts are natural and unavoidable — an assumption that pretty much drives the superhero genre.

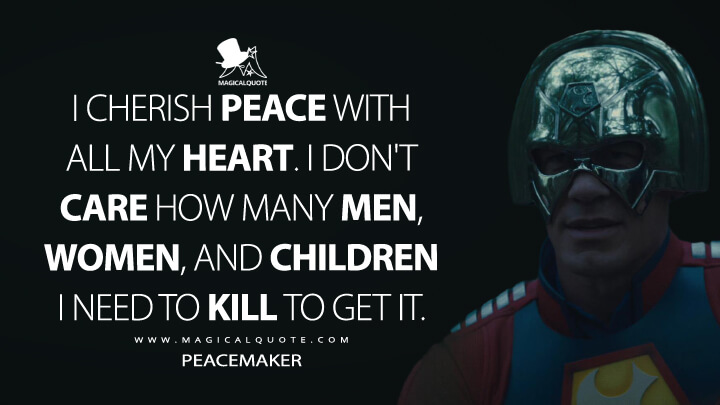

Superhero stories often carry a major normative adversarial assumption that we rarely question: that the protagonists are justified in using violence to bring about peace. Very generally speaking, the superhero genre presents a pretty simple narrative where “good” prevails over “evil.” Even when these narratives present good and evil as more ambiguously fluid concepts, the story’s resolution remains closely tied to the outcome of a physical confrontation between the superhero protagonist and his or her nemesis.

But fighting violence with violence is like fighting fire with fire — the only possible outcome is more violence/fire. DC’s Peacemaker has one of my favorite bits of dialogue that exposes the absurdity and unsustainable nature of this framework when he says “I cherish peace with all my heart. I don’t care how many men, women, and children I need to kill to get it.” A humorous turn of phrase that reveals Peacemaker’s Quixotic quest. How can there ever be peace if he keeps killing men, women, and children?

Normative adversarialism encourages a lack of coherence between the values we claim to hold – such as a superhero’s commitment to peace – and the actions we take to solve our problems – such as physically assaulting the peace-breakers. Superhero franchises reveal as much to us with every additional sequel: the peace they fight so hard to achieve by the end of one movie is broken with the release of a sequel. It’s the idea that the ends justify the means (i.e. peace is an important-enough ends to justify violence), as opposed to making sure that the ends and the means are coherent (i.e. peace must be brought about by peaceful acts).

In Eternals, Ikaris represents that (masculine) normative adversarialism. The drive to accomplish the goal no matter the cost — even if the cost is literally every single life on the planet. He believes firmly in that mission, even going so far as murdering his former leader, Ajak. Sersi represents the (feminine) opposite – mutualism. The idea that the only way to achieve lasting sustainable change is to engage according to different rules from those who are causing the wars and the violence. “This violent cycle has to end,” she states at one point in the film, confirming her realization that violence only begets more violence. In the midst of all that violence, she chooses peace, empathy, compassion, and creation.

Sersi and the Makings of a Leader

The final tension I want to get into has to do with the qualities of a good leader. For thousands of years, Ajak leads the Eternals. The other nine clearly trust her, respect her, and look to her for guidance and hope. At some point in the past not shown on screen, Ajak reveals the truth of their mission to Ikaris. When he sees her a week before Earth is to be destroyed, she tells him they must come back together to stop it from happening — to go against their creator. In response, Ikaris mercilessly throws her to the Deviants, who take her power, evolve, and kill her in the process. Ajak allowed empathy to guide her, had a change of heart, and was murdered for it.

What becomes abundantly clear is that, in her absence, the rest of the Eternals look to Ikaris to lead them. But why? Ikaris displays all of the traits most valued according to a more masculine framework. He is strong, fast, stoic, doesn’t seek out anybody’s help, and is physically unstoppable. If the Eternals’ driving purpose is defeating Deviants at all costs, then he clearly has the powers most aligned with that goal. And many of the Eternals seem to feel that way, too, including Ikaris himself.

When Sersi and Sprite find Ajak’s body, a sphere – which allowed her to speak with the Celestial Arishem – comes out of Ajak and goes into Sersi; a clear indication that she is the chosen successor. When they reunite with the others, Sprite tells everyone that Ajak chose Sersi, and Ikaris looks surprised/skeptical. Later, when the team talks about the Avengers and who might lead them now that Steve Rogers and Iron Man are gone, Ikaris, Kingo, and Gilgamesh have the following exchange:

Ikaris: I could lead them. I figure I’d be good at that.

King: Yeah you would.

Gilgamesh: Ajak didn’t even choose you to lead us!

And they carry on like it’s all part of their playful banter, even though it clearly hurts Ikaris. It also reveals Kingo’s admiration of Ikaris, whom he insists on calling “boss” the entire time, knowing full well that Sersi is Ajak’s chosen successor. Even Sprite, who has been Sersi’s companion all along, turns on her in favor of Ikaris. As Sersi struggles with the final decision to stop the Celestial, Sprite turns to Ikaris and says “forget who Ajak chose. You’re the strongest. You should be making this decision.”

According to the masculine forces which have dominated the world so far, Ikaris is the clearest choice to lead the Eternals. But, the balance is shifting. “The new age will be an age less masculine and more permeated with the feminine ideals, or, to speak more exactly, will be an age in which the masculine and feminine elements of civilization will be more evenly balanced. The time for Ikaris and his ilk to be the leaders of men has run its course. It’s time for a different kind of leadership. One that is characterized by empathy, by compassion, by collaboration, by creativity. And there is only one Eternal that already has those powers: Sersi. Ajak saw this in her, knew this about her, and trusted that eventually she might see it in herself. It takes a while, but Sersi finally comes to embrace her role, takes swift and dramatic action, and stops the Celestial from emerging in a manner that befits her leadership style: not by doing things herself, but by drawing on everyone’s powers, together. She isn’t strong enough on her own, isn’t afraid to admit this, and leans on the strengths of her team to complete their mission.

And if that weren’t enough, Sersi shows us one final act of empathetic, compassionate, and forgiving leadership after Sprite betrays her. While Sersi tries to stop the new Celestial from emerging, Sprite – who chooses to align with Ikaris after centuries of devoted friendship with Sersi – literally stabs her in the back. She explains how she has always envied Sersi, how much she hates the fact that she’s physically never able to grow up, etc. One could see how if this had happened to Ikaris, he would have been pretty merciless in his retaliation. But not Sersi. Once the emergence of the new Celestial is stopped, Sersi approaches Sprite and offers to use her newfound powers to give her what she’s always wanted: mortality. Once again, Sersi shows forgiveness, compassion, and restoration.

That is the kind of leadership the world needs. Not a self-centered, adversarial, impersonal, and uncaring leadership concerned only with winning, with being the strongest in physical terms only, and with bulldozing everyone else’s interests and needs for one’s own. But an empathetic, caring, compassionate, thoughtful, forgiving, humble leadership that values the collective good over the individual, concerns itself with everyone’s wellbeing, and will not rest until everyone can experience justice and fairness. Blend that with moderate and appropriate amounts of conviction, integrity, and initiative, and we may just find the balance and equilibrium that the world so desperately needs.

So What?

The masculine and feminine elements are two sides that exist in each and every one of us. But instead of finding a way for them to co-exist, most of us (and especially men) are encouraged to pit these two sides of ourselves against each other, with one typically neglected, and the other overfed. In reality, though, we need to see the ways they each give and take, flow together, keep each other in check, guard each other from extremes, and balance each other out for the healthiest expressions. We need to see, in other words, how the masculine and the feminine live in each and every one of us. And how it’s the acknowledgement of both of these sets of powers that will allow us to live our lives to the fullest, to experience human emotions to the greatest extent.

Balancing the two forces is the natural order of things, and refusal to allow that balance may literally kill us. Just look at Ikaris. By the end of the conflict, he has turned on the other Eternals, attacked them all, used all of his impressive powers, and still lost. That is how he sees it. It was a clear zero-sum game, and he’s the loser. If he allowed some of the feminine to balance out the masculine extremes within him, he may have still had a place among the Eternals. But it’s literally too much for him. Unlike Sprite, who found her way back into the fold, the internal tension is too much for Ikaris, and he solves his problem the only way he knows how: by meeting it with violence. Instead of reflecting on his poor choices, apologizing, attempting to restore and rebuild, Ikaris kills himself by flying straight into the sun. That is not a sustainable change. That is a quick “fix” without any sort of real accountability.

To further ground this idea of balance, let’s talk about one of the oldest and most powerful symbols of duality: the yin-yang. Yin and yang represent the need for opposing forces to come together in harmony in order for their powers to be fully realized. Yin represents the dark, the moon, water, coldness, softness, passiveness, stillness, intuition, and — you guessed it — the feminine. Yang represents light, the sun, fire, warmth, hardness, activeness, movement, logic, and of course — the masculine. The curved line in the middle represents the dynamic movement and flow of energies between the two sides — a give and take that goes on eternally. Within each side, you also find a spot of the opposing color, used to symbolize how neither side is absolutely just one or the other at all times. Each side always contains some of the opposite within it.

I love to use this imagery for thinking about the masculine and the feminine inside each of us. As men, society often encourages us to think of ourselves as only yang, all light, all fire, all hardness and logic and brute strength all the time. That we shouldn’t even allow the smallest amounts of yin into our lives. That is what Ikaris represents. Men are taught by the world to reject that internal balance and harmony, creating imbalance, disequilibrium, and all kinds of internal tensions and disconnection. It’s why so many men feel so angry all of the time, why they feel so lost, and alone, and misunderstood (like Ikaris, who disappeared for centuries in his angst). Sersi, meanwhile, represents the other side of the equation. It is through her particular strengths and leadership style that the world will move closer towards an equilibrium of both forces.

Because the reality is we are all of these things all of the time. We all have the yin and the yang, the masculine and the feminine, in us at all times. And our true self can only be found in the harmonious co-existence of our yin and our yang, in the acknowledgement that there is more to us than just all the most simplified stereotypical ideas of masculinity or femininity. We are complex humans, with all kinds of feelings, emotions, and thoughts. And they are all valid. And they are all beautiful. And they are all you. And they are all me.

We’ve tried being dominated by masculine forces for generations, and look where that’s gotten us — wars, starvation, environmental destruction, and slipping ever closer to fascism. It’s time for a new age, one in which, as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá states, the masculine and feminine elements of civilization will be more evenly balanced. And I, for one, can’t wait to see all of the amazing things we’ll achieve if we truly open ourselves up to that possibility. Eternals gives us a glimpse of that possibility, which is why – even with all its flaws – I think it may just be the most interesting and important Marvel movie ever made.

Discuss!